IPFS Introduction by Example

IPFS (InterPlanetary File System) is a synthesis of well-tested internet technologies such as DHTs, the Git versioning system and Bittorrent. It creates a P2P swarm that allows the exchange of IPFS objects. The totality of IPFS objects forms a cryptographically authenticated data structure known as a Merkle DAG and this data structure can be used to model many other data structures. We will in this post introduce IPFS objects and the Merkle DAG and give examples of structures that can be modelled using IPFS.

IPFS Objects

IPFS is essentially a P2P system for retrieving and sharing IPFS objects. An IPFS object is a data structure with two fields:

Data- a blob of unstructured binary data of size < 256 kB.Links- an array of Link structures. These are links to other IPFS objects.

A Link structure has three data fields:

Name- the name of the Link.Hash- the hash of the linked IPFS object.Size- the cumulative size of the linked IPFS object, including following its links.

The Size field is mainly used for optimizing the P2P networking and

we’re going to mostly ignore it here, since conceptually it’s not

needed for the logical structure.

IPFS objects are normally referred to by their Base58 encoded

hash. For instance, let’s take a look at the IPFS object with hash

QmarHSr9aSNaPSR6G9KFPbuLV9aEqJfTk1y9B8pdwqK4Rq using the IPFS

command-line tool (please try this at home!):

> ipfs object get QmarHSr9aSNaPSR6G9KFPbuLV9aEqJfTk1y9B8pdwqK4Rq

{

"Links": [

{

"Name": "AnotherName",

"Hash": "QmVtYjNij3KeyGmcgg7yVXWskLaBtov3UYL9pgcGK3MCWu",

"Size": 18

},

{

"Name": "SomeName",

"Hash": "QmbUSy8HCn8J4TMDRRdxCbK2uCCtkQyZtY6XYv3y7kLgDC",

"Size": 58

}

],

"Data": "Hello World!"

}

The reader may notice that all hashes begin with “Qm”. This is because

the hash is in actuality a multihash, meaning that the hash itself

specifies the hash function and length of the hash in the first two

bytes of the multihash. In the examples above the first two bytes in

hex is 1220, where 12 denotes that this is the SHA256 hash

function and 20 is the length of the hash in bytes - 32 bytes.

The data and named links gives the collection of IPFS objects the structure of a Merkle DAG - DAG meaning Directed Acyclic Graph, and Merkle to signify that this is a cryptographically authenticated data structure that uses cryptographic hashes to address content. It is left as an excercise to the reader to think about why it’s impossible to have cycles in this graph.

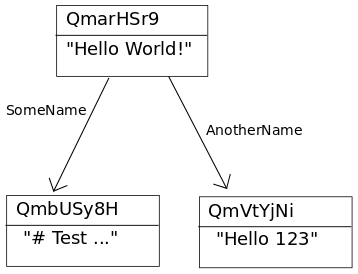

To visualize the graph structure we will visualize an IPFS object by a

graph with Data in the node and the Links being directed graph

edges to other IPFS objects, where the Name of the Link is a label

on the graph edge. The example above is visualized as follows:

We will now give examples of various data structures that can be represented by IPFS objects.

File systems

IPFS can easily represent a file system consisting of files and directories.

Small files

A small file (< 256 kB) is represented by an IPFS object with data being the file contents (plus a small header and footer) and no links, i.e. the links array is empty. Note that the file name is not part of the IPFS object, so two files with different names and the same content will have the same IPFS object representation and hence the same hash.

We can add a small file to IPFS using the command ipfs add:

chris@chris-VBox:~/tmp$ ipfs add test_dir/hello.txt added QmfM2r8seH2GiRaC4esTjeraXEachRt8ZsSeGaWTPLyMoG test_dir/hello.txt

We can view the file contents of the above IPFS object using ipfs cat:

chris@chris-VBox:~/tmp$ ipfs cat QmfM2r8seH2GiRaC4esTjeraXEachRt8ZsSeGaWTPLyMoG Hello World!

Viewing the underlying structure with ipfs object get yields:

chris@chris-VBox:~/tmp$ ipfs object get QmfM2r8seH2GiRaC4esTjeraXEachRt8ZsSeGaWTPLyMoG

{

"Links": [],

"Data": "\u0008\u0002\u0012\rHello World!\n\u0018\r"

}

We visualize this file as follows:

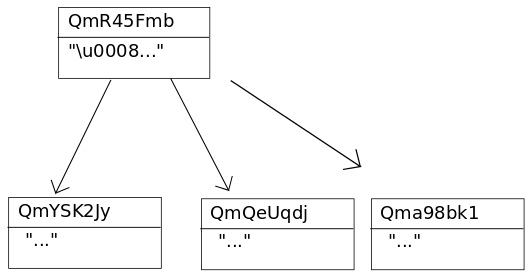

Large files

A large file (> 256 kB) is represented by a list of links to file chunks that are < 256 kB, and only minimal Data specifying that this object represents a large file. The links to the file chunks have empty strings as names.

chris@chris-VBox:~/tmp$ ipfs add test_dir/bigfile.js

added QmR45FmbVVrixReBwJkhEKde2qwHYaQzGxu4ZoDeswuF9w test_dir/bigfile.js

chris@chris-VBox:~/tmp$ ipfs object get QmR45FmbVVrixReBwJkhEKde2qwHYaQzGxu4ZoDeswuF9w

{

"Links": [

{

"Name": "",

"Hash": "QmYSK2JyM3RyDyB52caZCTKFR3HKniEcMnNJYdk8DQ6KKB",

"Size": 262158

},

{

"Name": "",

"Hash": "QmQeUqdjFmaxuJewStqCLUoKrR9khqb4Edw9TfRQQdfWz3",

"Size": 262158

},

{

"Name": "",

"Hash": "Qma98bk1hjiRZDTmYmfiUXDj8hXXt7uGA5roU5mfUb3sVG",

"Size": 178947

}

],

"Data": "\u0008\u0002\u0018��* ��\u0010 ��\u0010 ��\n"

}

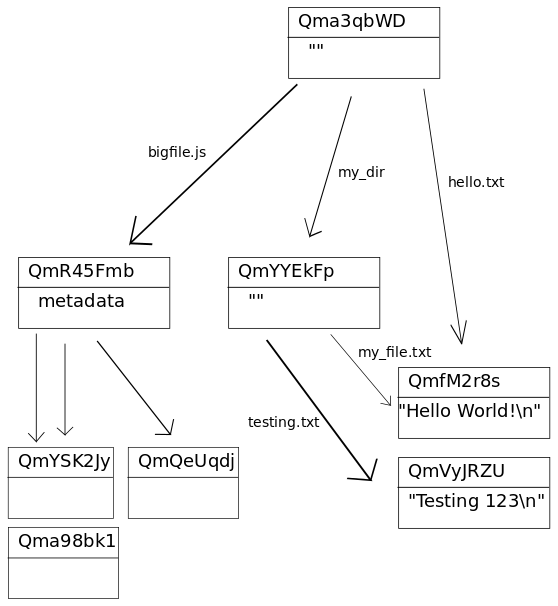

Directory structures

A directory is represented by a list of links to IPFS objects representing files or other directories. The names of the links are the names of the files and directories. For instance, consider the following directory structure of the directory test_dir:

chris@chris-VBox:~/tmp$ ls -R test_dir test_dir: bigfile.js hello.txt my_dir test_dir/my_dir: my_file.txt testing.txt

The files hello.txt and my_file.txt both contain the string Hello World!\n. The file testing.txt contains the string Testing 123\n.

When representing this directory structure as an IPFS object it looks like this:

Note the automatic deduplication of the file containing Hello World!\n, the data in this file is only stored in one logical place in IPFS (addressed by its hash).

The IPFS command-line tool can seamlessly follow the directory link names to traverse the file system:

chris@chris-VBox:~/tmp$ ipfs cat Qma3qbWDGJc6he3syLUTaRkJD3vAq1k5569tNMbUtjAZjf/my_dir/my_file.txt Hello World!

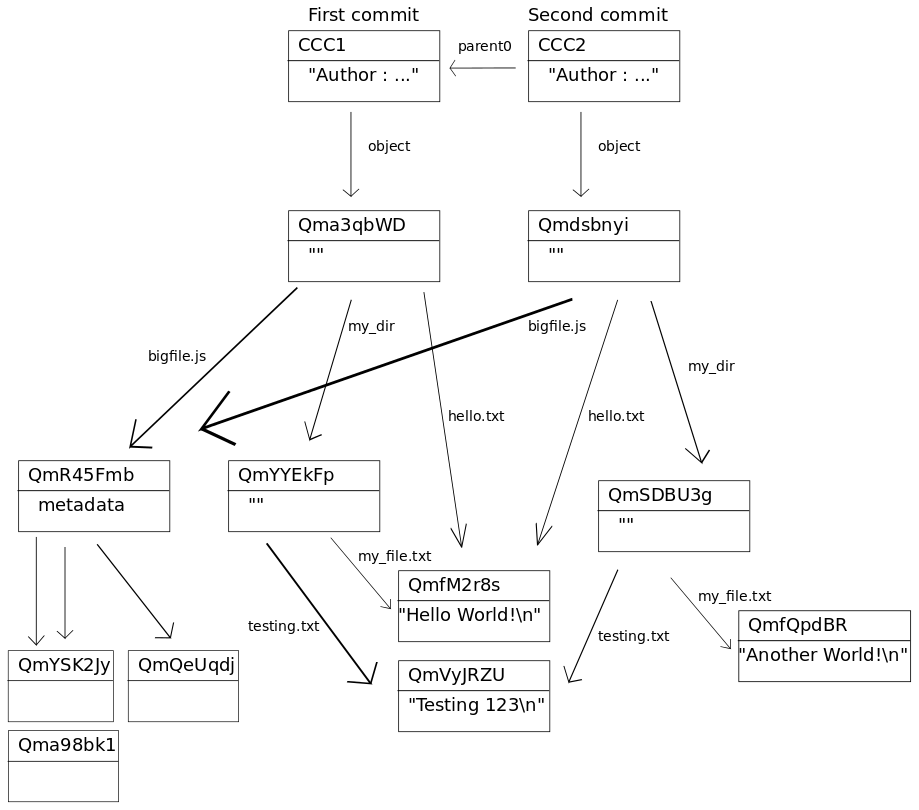

Versioned file systems

IPFS can represent the data structures used by Git to allow for versioned file systems. The Git commit objects are described in the Git Book. The structure of IPFS Commit object is not fully specified at the time of this writing, the discussion is ongoing.

The main properties of the Commit object is that it has one or more links with names parent0, parent1 etc pointing to previous commits, and one link with name object (this is called tree in Git) that points to the file system structure referenced by that commit.

We give as an example our previous file system directory structure, along with two commits: The first commit is the original structure, and in the second commit we’ve updated the file my_file.txt to say Another World! instead of the original Hello World!.

Note also here that we have automatic deduplication, so that the new objects in the second commit is just the main directory, the new directory my_dir, and the updated file my_file.txt.

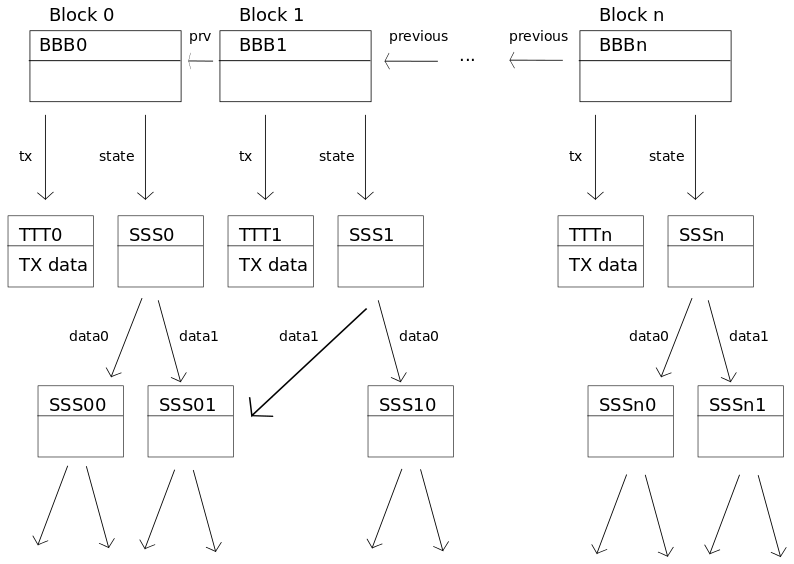

Blockchains

This is one of the most exciting use cases for IPFS. A blockchain has a natural DAG structure in that past blocks are always linked by their hash from later ones. More advanced blockchains like the Ethereum blockchain also has an associated state database which has a Merkle-Patricia tree structure that also can be emulated using IPFS objects.

We assume a simplistic model of a blockchain where each block contains the following data:

- A list of transaction objects

- A link to the previous block

- The hash of a state tree/database

This blockchain can then be modeled in IPFS as follows:

We see the deduplication we gain when putting the state database on IPFS - between two blocks only the state entries that have been changed need to be explicitly stored.

An interesting point here is the distinction between storing data on the blockchain and storing hashes of data on the blockchain. On the Ethereum platform you pay a rather large fee for storing data in the associated state database, in order to minimize bloat of the state database (“blockchain bloat”). Thus it’s a common design pattern for larger pieces of data to store not the data itself but an IPFS hash of the data in the state database.

If the blockchain with its associated state database is already represented in IPFS then the distinction between storing a hash on the blockchain and storing the data on the blockchain becomes somewhat blurred, since everything is stored in IPFS anyway, and the hash of the block only needs the hash of the state database. In this case if someone has stored an IPFS link in the blockchain we can seamlessly follow this link to access the data as if the data was stored in the blockchain itself.

We can still make a distinction between on-chain and off-chain data storage however. We do this by looking at what miners need to process when creating a new block. In the current Ethereum network the miners need to process transactions that will update the state database. To do this they need access to the full state database in order to be able to update it wherever it is changed.

Thus in the blockchain state database represented in IPFS we would still need to tag data as being “on-chain” or “off-chain”. The “on-chain” data would be necessary for miners to retain locally in order to mine, and this data would be directly affected by transactions. The “off-chain” data would have to be updated by users and would not need to be touched by miners.

blog comments powered by Disqus